PACIFIC PALISADES, United States — “Smushy concrete, that’s my technical term for it.”

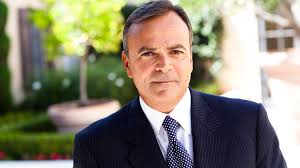

Rick Caruso, the Los Angeles-based developer behind some of the most productive shopping malls in the world, is standing in dirt, the ground dug up. In a little over a month’s time, the building with the “smushy concrete” façade will be a retail store, one of dozens inside Palisades Village, a roughly 125,000-square-foot shopping centre Caruso has built from the ground up in Pacific Palisades, a chi-chi neighbourhood on the west side of the city between Santa Monica and Malibu, where the median home value is over $3 million.

Some of the building facades are made of clean-white brick, others have the handmade look of the one Caruso is admiring. He’s smitten, even though smushy concrete does not come cheap, or easy. A billionaire who many believe will one day run for mayor of Los Angeles — something he doesn’t rule out — Caruso has spent an estimated $200 million building Palisades Village over the past two years.

If the project is a success, it could transform the area, which, despite its tony reputation, lacks a critical mass of restaurants, retail and other modern amusements.

“We’re in the business of building these spaces that we want people to come and enjoy and be happy,” says Caruso, whose leading-man tan — combined with a slick, can-do disposition — gives him a certain Old Hollywood panache. “If that’s your premise, then all of a sudden spending a little more money on real brick and real limestone — and having smushy concrete — is okay.”

Caruso’s track record is impressive. Consider The Grove, his pièce de résistance, the 600,000 square-foot shopping-centre-as-amusement park next to the CBS Studios lot in Mid-City, where 90 percent of visitors buy something and sales average $2,200 per square foot. (Opened in 2002, it’s one of the most-productive shopping centres in the US, second only to Miami’s Bal Harbour, where sales densities average over $3,000 per square foot.)

With its just-right mix of high-low retail (Barneys New York and Nordstrommingling with Topshop and Madewell) and cinematic experiences (trolley rides all year ‘round, artificial snow falls during the holidays), it’s a magnet for locals and tourists alike that has adapted more quickly to shifting consumer tastes and needs than many of its competitors.

“People have written endlessly about how the grove has a Disneyesque feel. Caruso was already [doing] experiential reality long before everyone else wanted to jump on the bandwagon,” says Garrick Brown, vice president of retail research for the Americas at Cushman & Wakefield. “Retailers are willing to pay the highest levels of rent there because it pays off. Experience drives foot traffic, it drives sales.”

But will Caruso be able to achieve the same success with Palisades Village? The project is smaller in square footage than many of his other projects, and decidedly more upscale. Several local designers, including jeweller Jennifer Meyer, Tamara Mellon and Anine Bing will operate alongside niche food purveyors — Sweet Laurel Bakery, McConnell’s ice cream shop — and mass players like Amazon Books.

“A lot of people are scratching their heads, but if you can deliver on experience…that’s the trick,” Brown says. “That’s what [Caruso] does, and that’s why his projects do so well.

Caruso is as confident in his strategy as he is in being ready to go for the September 22 opening date. (When we meet in mid-August, not a single store is even close to being move-in ready.) While he’s certainly a proponent of so-called experiential retail, he says that his fundamental approach has not wavered over time, even as technology has disrupted the shopping experience as we know it. One in four US malls won’t exist by 2022, according to a June 2017 report by Credit Suisse, and we will continue to see consolidation, especially at the lower-end of retail in what insiders call “Class C” malls. “There are a number of categories of retail where we’ve yet to see disruption,” Brown says.

At the same time, according to Brown, “Class A” malls, and some “Class B” malls, continue to draw customers, and he doesn’t see that changing any time soon — especially if they keep upgrading the experience.

Which is, of course, Caruso’s specialty. “I have a theory that I operate on, and the theory is that humans have never changed since the beginning of mankind,” the developer says matter-of-factly. “The things that were important in the beginning of mankind are still important today.”

But how does that translate into real results? “The key element is thinking of retail as hospitality and underscoring the human element,” says Kelsey Groome, managing director at Traub, a retail consultancy.

Here, Caruso shares his approach to building the world’s most successful shopping centres.

Put locals first. While destination shopping still exists, Los Angeles’ crippling traffic problem has made room for more localised experiences, which is why Palisades Village is populated with brands that align with the community’s needs, not the whims of tourists stopping by after a day at the beach.

“People put a premium on walkability,” Caruso says. “They’re excited that they don’t have to drive. You get a good meal or a movie and the kids get to stay close.” Caruso, of course, is not the only developer to take this approach. Neighbourhood-driven shopping centres and streets now dominate retail everywhere from Atlanta’s Westside Provisions to Minneapolis’ North Loop, reflecting the “back-to-the-city” movement sweeping the nation’s major metropolises. (People want to live in places where they can walk more than they drive.)

Build the best version of real life. In the case of Palisades Village, Caruso is redeveloping what was already zoned as a business district, with real roads. (His ideal retail strip is Bleecker Street in New York’s West Village, which was in decline for several years but is currently being redeveloped by Brookfield Property Partners.) But even in brand-new developments, the executive says it’s crucial to keep that feeling of an authentic pedestrian walkway alive. For instance, at The Grove, the sidewalks have curbs and gutters. He argued over the point with the project’s landscape architect, who was worried shoppers would trip.

“I said, ‘Based on your theory, people should be tripping all over the world right now’. If I don’t build the curb and gutter, the guest’s eye will never think they’re on a real street,” he says. “If I don’t put the little crown in the street and have a gutter on the end of that where the water’s going off, all I’m doing is building a plaza. We go around the world and we study those details of what’s worked historically.”

Data drives results. A public supporter of Amazon, Caruso increasingly recruits data-driven direct-to-consumer upstarts into his properties. “Traditional brick-and-mortar retailers lost focus on their customer. They became so uniform in terms of how they were merchandising stores across the country and it doesn’t make any sense,” he says. “They’re going out of business for a reason. The way you merchandise a store in Los Angeles and how you merchandise a store in Milwaukee: why would it be the same?”

Caruso’s own team collects data through everything from WiFi beacons to parking and Uber check-ins to help better understand traffic patterns and visitor behaviour.

Community relationships count. While Caruso received pushback regarding Palisades Village from some locals early on — two small business owners sued the organisation in 2016, claiming that construction disrupted sales in their own nearby retail stores — the community has generally been welcoming and supportive of the project. (The lawsuit was resolved.)

Caruso’s long-term dealings with civic leaders also helped moved Palisades Village forward more quickly.

For instance, Caruso was able to build the project on what the city calls a “mitigated negative declaration,” which is an exemption from submitting an Environmental Impact Report, which can take more than 18 months to draft.

“You have to know demographics, you have to know psychographics, you have to have relationships,” he says. “If you were from the outside, this would have taken years. We got it approved in less than 12 months.”

Rethink store formats. “Everything is really tiny,” Caruso says of the centre’s stores, which average 2,200 per square feet. (For instance, a typical Sephora may be 7,000 or 8,000 feet. At Palisades Village, the Sephora Studio is only 3,000 square feet.) Inventory storage is built below ground so retailers can use main floor operations for selling and customer activations, such as a lounge or barista counter, only.

A smaller space often means taking a different approach to inventory altogether: Now that physical retail is more about touching and feeling a product and less about actually procuring it, retailers are increasingly experimenting with the “showroom model.”

Every tenant must pay rent. In the US, many developers offer free rent to young brands in hopes of wooing more established ones, and then hike up the prices once paying customers are plentiful. Caruso claims he doesn’t play that game, but instead charges a fair rent — and a sales percentage on top of that — in exchange for marketing support on his side.

“We want to have retailers and restaurateurs on our property that are going to be highly profitable and productive,” he says. “It’s about the sum of the parts. We can drive marketing and we can push traffic in and out. Things go south when pricing and revenue are disconnected.”